Embodied carbon is the sum of greenhouse gas emissions released during the following life-cycle stages: raw material extraction, transportation, manufacturing, construction, maintenance, renovation, and end-of-life for a product or system.

Embodied carbon is reported as global warming potential (GWP) and is measured relative to the impact of one molecule of carbon dioxide, usually over a 100-year time-frame. One kilogram of carbon dioxide has a GWP of 1 kgCO2e, whereas, for example, one kilogram of methane is approximately 28 kgCO2e.

CO2e emissions released before the building or infrastructure use begins is sometimes referred to as upfront carbon. Upfront carbon is projected to account for half of the entire carbon footprint of new construction between now and 2050, threatening to consume a large part of our remaining carbon budget without even accounting for maintenance, renovation, and end-of-life embodied carbon emissions.

Embodied carbon is different from embodied energy, which only accounts for the energy use in all life-cycle phases of the built asset, regardless of energy source. Some amount of embodied energy may be from renewable sources and would not be considered a source of greenhouse gas. Net embodied carbon calculations may include carbon sequestration and end-of-life considerations. Estimating end-of-life impacts is challenging due to their uncertainty at the time of design and construction.

It goes without saying that material efficiency is a tenet of structural engineering best practices regardless of assessing environmental impacts or not. One might think that more materials would equate to more cost, but oversizing often happens to simplify production and construction, which also reduces cost. Structural engineers also often unknowingly chose higher embodied carbon materials because they save time or cost for the project. These norms are starting to change however.

Assessing environmental impacts of structural materials is becoming part of the decision matrix, and material quantities and the impacts of those materials are coming under closer scrutiny. Structural engineers today and of the future must understand how their designs not only impact architecture, MEP, cost, and constructibility, but also the environment.

All structural materials have different environmental impacts and design decisions made throughout a project, do in fact have an impact on a building or bridge’s overall environmental impact. Life cycle assessment (LCA) is how structural engineers can measure this impact.

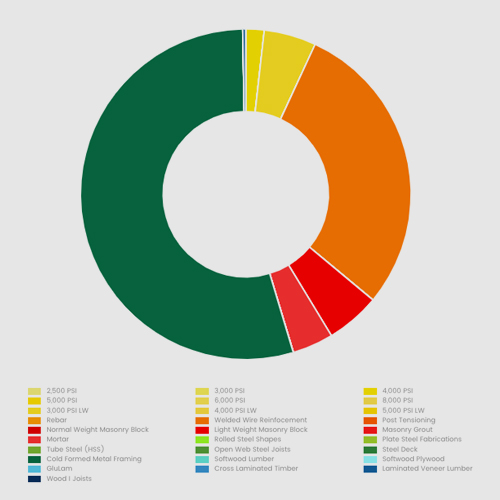

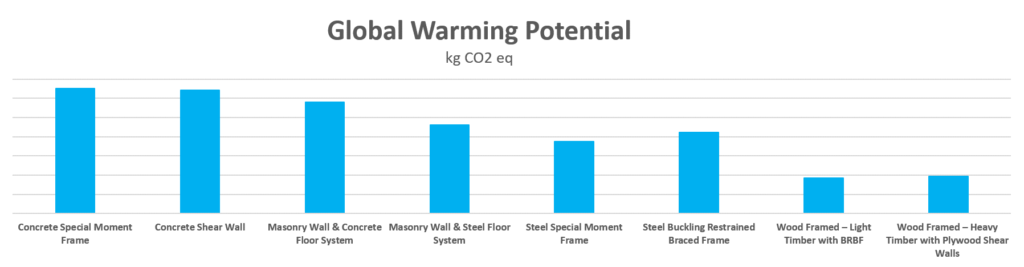

A study published in the 2013 SEAOC Convention Proceeding illustrates just this. This study looked at 8 different structural/seismic systems (two concrete, two masonry, two steel, and two timber) for a prototype 5-story office building in Los Angeles, CA to assess the relative environmental impacts of these functionally equivalent alternative designs. The study focused on the structural systems in isolation and did not address the non-structural impacts or operational impacts. For each structural/seismic system, the study used a building of the same size and dimension, with the same column layout, core area layout, perimeter curtain wall system, and equivalent floor quality in terms of sound-proofing and solidness. While for some materials, this did not produce the most efficient structural designs, it was how the authors decided to create functionally equivalent buildings. This study found that the timber buildings generally had significantly less impact (on the order of 3 times less) than the steel buildings and the steel buildings generally had less impact than the concrete and masonry buildings. While this was the case for this particular study, no general conclusions should be made about which material is the most environmentally efficient. Instead it points out that in fact structural systems do have different environmental impacts and that LCA should be used to account for these differences. LCA should be used to improve a structural design once a primary system is chosen.

Embodied carbon impacts of a building’s structural system are primarily associated with the different life cycle stages: material extraction, manufacturing and production, construction, damage and repair during service life, and end-of-life considerations.

There are many opportunities for structural engineers to reduce the embodied carbon of buildings. Please refer to SE 2050’s guidance for structural design and procurement for recommended practices.

Below are some resources for getting started with embodied carbon:

Industry Leadership on Embodied Carbon

Webinars

Books (purchase required)

Articles