Click on image below for a PDF version of this top ten list.

1. Concrete masonry assemblies can be a lower embodied carbon form of concrete construction.

Concrete Masonry Units (CMU) are manufactured to optimize material efficiency. The dry-cast concrete process uses less water and cement, and the hollow shape of the units further reduces embodied carbon by minimizing material volume when not fully grouted. CMU’s manufacturing process gives CMU a unique void structure within the concrete itself that enables increased amounts of CO2 to be absorbed deeper into the matrix at relatively fast rates through a chemical reaction called carbonation. Research indicates that typically 21% of the calcination emissions originally released from the limestone during the manufacturing of the cement are reabsorbed through carbonation by the time CMU leaves the manufacturing facility. Research and modeling suggest the CO2 uptake could offset up to 25% of CMU’s upfront embodied carbon within 20–25 years. CMU carbonation during manufacturing is reflected in the industry average CMU Environmental Product Declaration (EPD). The Prestandard for Assessing the Embodied Carbon of Structural Systems for Buildings outlines the recommended approach for including CMU carbonation in the use phase.

2. Two main factors drive the embodied carbon of CMU block: strength and type of lightweight aggregate.

The US Industry average CMU EPD published August of 2024 categorizes the two main factors affecting the embodied carbon of CMU. These factors include the strength of the CMU (higher strengths require more cement) and the type of lightweight aggregate used for lower density units. Lightweight aggregate can either be manufactured, such as expanded shale, or can be naturally occurring, such as pumice and scoria. Manufactured lightweight aggregate has higher embodied carbon than naturally occurring aggregate because of the energy required for production. The CMU industry average EPD reports that the Global Warming Potential (GWP) for lightweight CMU using manufactured light weight aggregate is approximately 40% higher than CMU using natural lightweight aggregate. It is important to note that the type of lightweight aggregate available to CMU producers varies by geographical region.

3. Optimize masonry assembly components.

Concrete masonry assemblies include CMU, mortar, grout, rebar, and sometimes joint reinforcement. One of the most effective ways to lower the embodied carbon of CMU assemblies is to maximize rebar and grout spacing. This helps to lower not only embodied carbon but also cost. Engineers may also consider the smallest depth block that can be used for the project. For non-seismic or low seismic areas vertical wall reinforcing can exceed 48 inches on center and can approach 120 inches on center in many cases. See the Masonry Assembly Components section of the Design Guidance page for additional information.

4. Reduce grout cement content.

To reduce cement content of grout, specify the compressive strength method rather than the volume method and consider specifying coarse aggregate in place of fine aggregate as defined in ASTM C476. Because masonry grout sees no performance gains from a higher compressive strength than the assembly f ’m, the goal is to use only as much cement as needed to bind the aggregate and keep it from separating. Grout can also be specified with Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCM) such as fly ash, slag, and ground glass pozzolans to replace cement with replacement rates as high as 50%. See the Specified Compressive Strength Method for Grout Section of the Specification Guidance page for additional information.

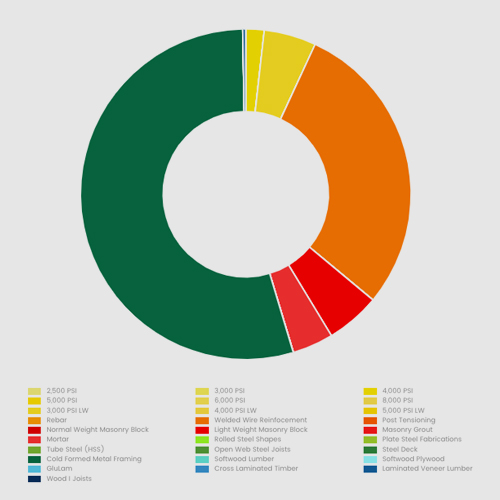

5. Evaluate strength of wall assembly materials.

CMU complying with the ASTM C90 minimum compressive strength requirement of 2000 PSI can be used for most applications. An assembly design strength (f ’m) requirement of 2000 PSI can be achieved using a CMU compressive strength of 2000 PSI and Type S mortar. Where structurally required, higher design strengths can be specified. In some cases, using higher-strength CMU —although they may have higher embodied carbon individually—can reduce the amount of reinforcement and grout required, thereby lowering the total embodied carbon of the wall assembly. Each scenario would need to be evaluated for the embodied carbon intensity of the wall assembly. See the Assembly Strength section of the Design Guidance page for additional information.

6. Consider the full range of structural concrete masonry applications.

When concrete masonry walls are reinforced for load-bearing applications, they can span taller unbraced lengths, support substantial gravity loads and serve as lateral force resisting elements. If vertical supports are required, columns can be built out of standard units and bond beams can be used over openings. Capitalizing on masonry’s full structural capabilities can eliminate redundant structural elements, streamline trades, and reduce construction-phase carbon and cost. See the Use Full Range of Structural Concrete Masonry Applications section of the Design Guidance page for additional information.

7. Align designs with standard CMU dimensions.

For maximum construction efficiency and economy, concrete masonry elements should be designed and constructed with a layout that considers the modularity of the units. If dimensions of openings, wall lengths, and wall heights adhere to an 8” module, units don’t need to be cut in the field, which helps to minimize labor costs, and lower embodied carbon by minimizing waste. Structural engineers can collaborate with architects to promote this approach when laying out the building. See the Modular Dimensioning section of the Design Guidance page for additional information.

8. Integrate structure and building envelope.

Masonry systems can be multi-functional serving as structure and building envelope so fewer materials are needed to meet performance and program requirements. When used at exterior wall locations, architecturally-finished CMU construction may also be part of the envelope system and provide the finished surface, reducing the need for additional cladding material. Since coatings and coverings can affect the rate of CMU carbonation and contribute additional embodied carbon to the wall assembly, design teams should incorporate these factors when developing embodied carbon assessments and comparing design options. Additionally, load bearing CMU walls eliminate the need for additional non-structural materials used as infill between structural framing.

9. Engineered masonry design is more efficient than empirical design.

Typical CMU details and schedules on construction drawings have historically been based on empirical design assumptions which may be overly conservative for the project. Empirical design methodology was removed from the IBC in 2021 and from TMS 402 in 2022 in favor of analytical design methodology. Consider creating project-specific schedules for each masonry element (wall, beam, partition, column, etc.). These might include separate bond beam tables for load bearing and non-load bearing walls and partition tables tailored to local seismic demands, leading to more efficient, lower embodied carbon designs. See the Engineered Masonry Design section of the Design Guidance page for additional information.

10. Material and construction innovations can reduce embodied carbon for concrete masonry construction.

There are several manufacturing and construction innovations that can reduce the embodied carbon associated with CMU construction. Strategies include mix design optimization, technologies encouraging more CO2 sequestration, and using non-traditional SCM such as ground glass and alternative cements. Also consider dry-stack structural walls which can be used for any application that regular CMU walls are used for, with the exception of fire rated assemblies (unless solidly grouted). Using this approach eliminates the need for mortar and can contribute to circularity of CMU construction by allowing for easier deconstruction and reuse of units.